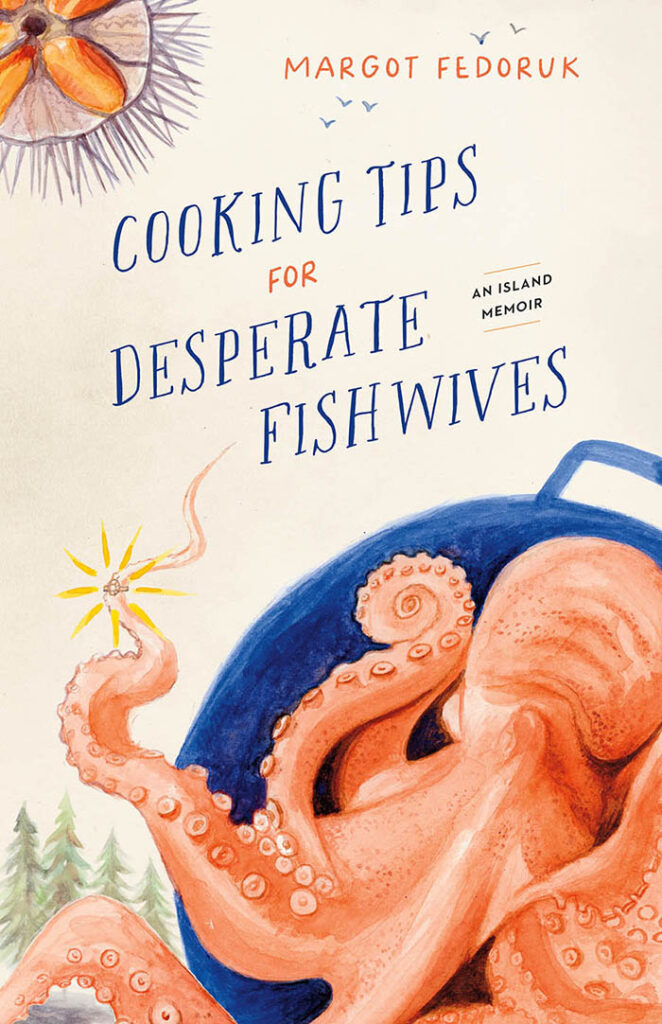

Excerpt from Cooking Tips for Desperate Fishwives: An Island Memoir, by Margot Fedoruk, Heritage House

Follow Margot on IG / FB / Twitter

“The night I ran over Rick with my car, I was over four months pregnant with our first daughter. I remember crouching at his side, knees painfully ground into the concrete, as I swayed over him in my grief. I didn’t know it then—that it was too late. An invisible cord was tethering us, not just me to the baby, but all of us wound up together, pulsing toward everything that came after.

Earlier that night, I had made a vegetarian lasagna. Rick was two hours late. I couldn’t call him from our rental suite because we had cancelled our phone service in advance of a move to our new condo, closer to downtown Victoria, near the Galloping Goose Trail.

I walked downstairs to call Rick from the suite below. It was occupied by an unhappy single mom. I often heard her yelling at her timid preschooler through the thin floors covered in shag carpeting running the length of the ’70s style rancher. She was a heavy woman, and I imagined her jowls shaking with the effort. I made no attempt to hide my emotions, bonded as we were under the same roof of sorrow.

She let me into her suite, unperturbed by my distressed state. Mothers, I surmised by her bemused expression, must ready themselves for disaster. I hardly registered much of the surroundings as I dialed Rick’s cell phone number, hands shaking, fingers still pungent with garlic. He was out for a drink at Sidney’s Blue Peter Pub with his crew after the dive. That night he had been seeking small green urchins found on the murky bottom of the ocean, surprisingly close to home for once. I told him not to bother coming home. He took this to mean he didn’t have to come back immediately.

Yet why didn’t he know? Most nights I couldn’t sleep for the baby kicking me in the bladder. I was sure my fat cells were multiplying each night as I lay sweating on the mattress. I could only take short shallow breaths while the baby dug into my diaphragm and Rick snored, oblivious to my discomfort.

I felt even more alone with that untouched, perfect lasagna. I flashed forward to my baby’s birth and everything that would come after. Who would be there for me then? My own mother had died when I was twenty-three years old, skeletal from cancer. She wasn’t there to warn me against marrying someone whose job takes them up and down the west coast for half of each year. Would I have listened if she had protested? Who listens to their mother when it comes to love?

RICK IS A WEST COAST URCHIN DIVER. The ocean is his element, where he is most at home. He is away for weeks at a time harvesting spiny sea urchins that in turn would feed our family. The painful urchin spines get lodged under the skin of his fingers and sometimes his pale freckled legs. He picks at them with a sewing needle he sterilizes with a red plastic lighter. I swear when I step on them, shocked to find them carelessly lodged in the loops of the carpet.

Some dives he catches a Puget Sound king crab and brings it home. The crab scrabbles at the sides of a taped-up Styrofoam cooler. It is Rick’s job to kill it with a swift knock to its thick shell, then to deftly slice it in half with a sharp knife. He turns its sweet flesh into mounds of crab cakes, which we feast on, hot and greasy from the pan. Afterward, we sit contentedly on the deck, my bare feet in his lap until the stars come out.

Rick has been a diver since he was nineteen. He has dived for geoducks (giant clams) blasted out of the ocean floor with a strong jet of water. He has collected scallops, sea cucumbers, giant Pacific octopus, and green and red sea urchins. Urchins are hand-picked from rocky crevices with a metal rake, custom fitted to his arm. He holds a large net bag in the other hand while he swims along the seabed up to eight hours a day.

“I make all my money by putting the red ball in the basket,” he likes to joke. His right forearm is huge, like the claw of a crab, from filling a 250-pound bag. It’s the same arm that will rock our infant daughter to sleep at night with such tenderness.

When I saw Rick finally drive up in his blue truck, I rushed to my car and cursed as I drove straight into his side door just as he was stepping out. I was blind with rage, perhaps more at my alcoholic father than at Rick. He fell to the pavement, orange hair splayed in the swaying shadows of the shifting tree branches. I ran to him, terrified that I had just killed the father of my unborn child.

When I called out to him, voice cracking, he opened his eyes, and said, “I’m okay. It’s alright. I’m okay.”

I swore at him with a fresh surge of anger. I hauled my body back into the car and sped off wildly, gravel spitting beneath the tires. Small rocks hit his bare legs as he stood dazed, watching me drive away into the night.

I drove to a nearby 7-Eleven and bought a pack of cigarettes, even though I had quit when I first found out I was pregnant. I rented a hotel room off Dallas Road with an ocean view, although I never opened the curtains. I smoked a couple of cigarettes zealously, then fell exhausted on the polyester bed cover, feeling sick and hungry. I wished I’d brought that lasagna.

I FEEL RICK’S ABSENCE MOST KEENLY AT NIGHT, imagining his powerful body moving in slow motion, silently like a crab, across the cold moonscape of the ocean floor. Even though I am not the one underwater, I feel like I am holding my breath, waiting for disaster. On nights like these, I hope my love will keep him safe. On the many, many nights like these, when I lie alone listening to the hum and chug of the refrigerator—the only sound in our island home—doubt creeps in. I wonder if the amount of pain in our relationship is equal to the amount of joy. Yet Ernest Hemingway said in A Moveable Feast, “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.” And what feasts we’ve had.

Killer Lasagna (Garlicky Vegetarian Lasagna)

Ingredients

- 1 whole garlic bulb

- Olive oil

- 1 large eggplant

- Salt

- 1 package 375-g dried lasagna noodles

Filling

- 11/2 cups chopped spinach and baby arugula lettuce mix or any greens you have handy, such as kale or Swiss chard

- 1/4 cup chopped parsley

- 1 egg

- 1 (500-g) container delicate, traditional ricotta cheese

- 11/2 cups mozzarella cheese

- 1/2 cup Parmesan cheese grated is best

Marinara sauce

- 3 Tbsp olive oil divided

- 1/2 lb mushrooms sliced

- 1 large white onion chopped

- 1 tsp salt plus more to taste

- 1 small green pepper chopped

- 1 zucchini diced

- 2 large garlic cloves minced

- 1 tsp pepper plus more to taste

- 1 tsp or so red chili flakes plus more for sprinkling

- 2 tsp dried basil

- 2 tsp dried or fresh oregano

- 1/4 tsp ground thyme or a sprig of fresh thyme leaves

- 2 (796 mL/28 oz) each cans canned plum tomato puree, crushed or diced

- 2 tsp balsamic vinegar

Finishing the lasagna

- 11/2 cups grated mozzarella cheese divided

- 1 cup grated Parmesan cheese divided

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 425°F. Cut a small amount off the top of the bulb of unpeeled garlic. Lightly toss garlic in a drizzle of olive oil and wrap in foil. Place bulb of garlic in the oven. Roast whole garlic while you are prepping and baking the eggplant. When the garlic is finished roasting (about forty minutes), let cool and then squeeze the softened cloves out of the skin and set aside.

- While garlic is roasting slice the eggplant lengthwise into thin 11⁄2 cm pieces Leave skin on and salt generously. Let the salted eggplant rest for 7 minutes to draw out the moisture, and then pat dry with a paper towel. Flip and salt eggplant pieces again. Wait another 7 minutes or so and pat dry once more. Once oven is preheated, add eggplant slices to a greased sheet pan and cook for 10−12 minutes on each side or until lightly browned. Remove pan from oven and set aside until it is time to layer. Turn oven temperature down to 375°F.

- Cook lasagna noodles in boiling water (add 1 Tbsp salt) until al dente (10 minutes or so). Drain and rinse pasta with cold water and toss with a bit of oil to prevent the noodles from sticking together.

For the filling

- Chop up the spinach, arugula, and parsley. In a bowl, beat the egg and mix into the ricotta cheese 1⁄2 cup of the Parmesan cheese. Stir the chopped greens and the 11⁄2 cups grated mozzarella into the ricotta mixture and refrigerate until you are ready to assemble.

For the marinara sauce

- Heat 2 Tbsp of olive oil in a large pot and fry up the mush- rooms for a few minutes, then add the onions and 1 tsp of salt and fry until soft. Next, add the chopped green pepper, zucchini, and minced garlic. Stir in the spices (pepper, chili flakes, basil, oregano, thyme) and canned tomatoes, plus balsamic vinegar and 1 more Tbsp of olive oil. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a simmer over medium-high heat for about 35 minutes or until the sauce has thickened. Stir with a wooden spoon. Never use a metal spoon in a tomato-based sauce. Season the sauce with more salt and pepper, if needed. Some people may find the Parmesan cheese adds enough salt, but a bit of extra saltiness brings out the robust flavours. For those who like a spicier sauce, add more black pepper, or sprinkle each portion with extra red chili flakes.

- If you haven’t already, grate your mozzarella and the additional Parmesan cheese and set aside until you are ready to assemble your lasagna.

- Find a large 13 × 9–inch casserole dish or, if you don’t have one, use a roasting pan which will allow plenty of room for all your layers, so the contents won’t overflow onto the bottom of the oven.

How to layer in order:

- Cover the bottom of the pan with about 1⁄2 cup marinara sauce.

- Add a layer of cooked lasagna noodles.

- Spread half of the ricotta cheese/mozzarella and greens mixture.

- Add the pieces of whole roasted garlic and spread evenly on top of the ricotta mixture. (Rough chunks of caramelized garlic dotted throughout the lasagna are a wonderful surprise to bite into.)

- Spread another layer of marinara sauce.

- Layer with slices of roasted eggplant, then sprinkle with 1⁄2 cup Parmesan cheese and (chili flakes optional).

- Add another layer of lasagna noodles.

- Layer with the rest of the ricotta/mozzarella cheese and greens mixture.

- Spread more marinara (about 1 1⁄2 cups).

- Add the final layer of lasagna noodles.

- Use up the rest of the marinara sauce.

- Top with the rest of the mozzarella cheese and remaining 1⁄2 cup of grated Parmesan.

- Bake for 20 minutes. Rotate the pan and bake for another 20 minutes. Remove from the oven and let set for at least 10 minutes. Dig in.